Contributions

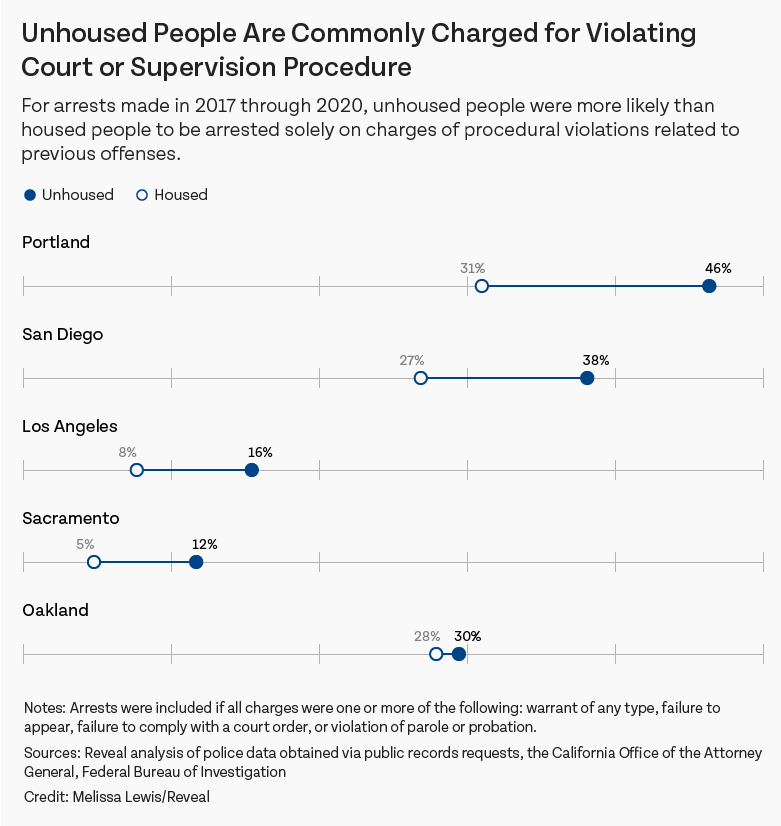

I analyzed more than one million arrest records provided by local law enforcement agencies in California, Oregon, and Washington, and interviewed more than 60 people (current and former law enforcement officers, lawyers, researchers, advocates, and unhoused people) for both the text story and radio show.

The criminalization of homelessness has a long history in the United States. It was embedded in the first British laws ported over here – one law regulated the existence of “vagabonds, idle and suspected persons” in public space. It also played a seminal role in the broken windows theory, which said that visible signs of disorder brought more serious crime and has dominated American law enforcement for decades.

“The unchecked panhandler is, in effect, the first broken window,” the theory’s authors wrote when introducing it in The Atlantic magazine 40 years ago.

I contributed to writing the radio script, and recorded much of the tape used in the show. I additionally narrated the radio/podcast episode and wrote the text story. If you’re here because you’re a journalist on a similar beat, please feel free to contact me for materials (books, academic articles, previous reporting) I consulted.